It’s day 24 of Domestic Violence Awareness Month for men and boys, the invisible victims of domestic violence. Today’s In His Own Words is an example of the systemic abuse to which men and boys are frequently subjected. It’s also an example of how many women use victimhood (real or imagined) as a form of street cred and/or social status.

It’s day 24 of Domestic Violence Awareness Month for men and boys, the invisible victims of domestic violence. Today’s In His Own Words is an example of the systemic abuse to which men and boys are frequently subjected. It’s also an example of how many women use victimhood (real or imagined) as a form of street cred and/or social status.

“My ex-boyfriend cheated on me. Yeah well, my husband beat me and I had cancer. My adopted third world son has soooo many behavioral issues, we have to give him meds that make him morbidly obese, it’s sooooooo hard on me. That’s nothing, I was raped by my college boyfriend. Big deal, I was molested by my father and gang raped by the marching band and have a deadbeat husband.”

I have personally witnessed this kind of “victim off” in academic settings, clinical staff settings and, most recently, at a friend’s birthday party — women trying to “out victim” each other. In other words, not in a therapeutic setting. These are women who were superficial acquaintances, colleagues and/or classmates, not intimate friends with who there was an established bond. It’s disturbing. Healthy individuals don’t want to be seen as victims, even if they have, in fact, been legitimately victimized.

Tim wanted to give back to his community by volunteering with a victim advocacy support agency. In the end, he became a victim of their bigotry and sexism.

Victimized by Victim Support Advocates

In my mid twenties, I was a shy, naïve, introverted, but equally idealistic young man. I had a steady job, but I was still finding out who I was and what I wanted out of life. I decided that there was more to me than technology, and I started looking for a more human way to contribute to society than mere economic activity.

Somehow, I found out about the work done by Victim Support, a volunteer organisation that helps victims of crime to recover from their experiences. They seemed a noble organisation, and volunteering my time to them seemed like a good way to do something positive for those for whom I felt empathy and compassion. So, I wandered down to the central police station (where their offices were co-located) and signed up.

First, I was interviewed to screen for unsuitable candidates. I was asked questions concerning my motivations and attitude towards crime. Memorably, I was asked whether I would be willing to work with victims of rape. The idea struck me as being singularly inappropriate: a man is likely to be the last person a freshly raped woman would want to talk to and, never having even heard of the red pill, I said so, but also that if that was what a victim wanted, then of course I would do what I could. Their response was that, “Well, men get raped, too”.

A charitable reading of this question and their reply was to check that I didn’t have anything in my past (such as sexual abuse) that dealing with rape victims might trigger though, cynically — especially in retrospect — I wonder if this wasn’t some sort of shibboleth to gauge how ‘rapey’ I was myself.

I was duly accepted into the next intake of basic training seminars, which involved three or four intensive weekend-long, 8 hours a day seminars. Most of it was lecture format with socialisation between sessions, but there were group activities as well. I was by no means the only male there but, at 25, I was certainly the youngest one, and the women outnumbered the men by something like 3:1.

The first sign that something was amiss was when I approached the convenor about the source of a passage that had been handed out the previous day. “Our deepest fear” so caught my attention that I looked it up to find out more and I discovered that, where the convenor had attributed it to Nelson Mandela, the original passage is to be found in Marianne Williamson’s book, “A Return to Love.” (That book and its related work, “A Course in Miracles” is deeply new-agey stuff that is somewhat extreme, even for most new-agers, and is a whole ‘nuther story.)

I felt that Williamson deserved to be correctly attributed, not least so that others whose interest it might catch could find out more, but the convenor wasn’t remotely interested. She certainly didn’t care for what was actually true, and I got the distinct impression that she was more concerned about not losing face in front of her class than accurate course materials (even though I spoke to the convenor privately between sessions rather than draw attention to the error in front of the rest of the class).

Still, ‘not that important,’ I thought, and I dismissed it as just a matter different priorities. Looking back, though, I wonder if there wasn’t something else going through her mind.

One of the group activities was an exercise in exploring our own pasts and, if I wished to be uncharitable, just a hint of a parade of victim credentials. Many of those there described experiences of domestic violence and sexual assault themselves, and I recall feeling ‘outclassed,’ almost as if I didn’t deserve to be there because nothing particularly bad had happened to me. The task was to draw a few symbols representing certain events in our past in each of the four quadrants of a shield-like thing on a piece of flip-chart paper which was then to be pinned up along with everybody else’s. These were then discussed as a group, and then we paired up for further discussion.

It’s not that I had no bad things in my past, but my father’s stroke and subsequent death (when I was aged 7 and 17 respectively) seemed fairly ordinary and unremarkable compared to some of the horrors described by the other students. What this was all in aid of, I’m unsure (particularly as the point was repeated time and again that support work is emphatically not therapy), but I am certain of the effect: it made me feel extraordinarily vulnerable, it brought unprocessed grief to the surface and tears with it, and I see no reason this would not be true for the other students.

I don’t remember much more detail of this except that the guy I paired up with, and who saw my grief, was a middle-aged, softly-spoken Canadian gentleman. I never did quite shake the feeling that we were constantly being evaluated, especially in that particular activity.

I think I got through most or all of the class work, and the next weekend we were scheduled to meet at the hospital for a tour of the areas and procedures we would be expected to know in the course of this work. At about 10:30am one weekday morning, I got a phone call from the softly-spoken Canadian. He said that he had something he needed to discuss with me, and could I meet him at the police station (VS’ base, and where the training sessions were held) at noon? Since it was only a 10 minute walk away, I agreed.

Immediately, I knew something was wrong. Why was a fellow student phoning me up and asking to meet at the police station? What was it that he couldn’t discuss over the phone? How, indeed, did he get my phone number, private information protected by law?

The softly-spoken Canadian gentleman turned out not to be a student at all, but rather a member of that chapter’s management board. He led me into a small room and baldly stated that a complaint had been laid against me by one of the women on the course. He would not say by whom (or even how many complaints), what the complaint was or what I was supposed to have done, only that my presence made the women ‘feel unsafe.’ I was given two choices: ‘voluntarily’ sign the provided letter of resignation (in which case the whole matter would be dropped and forgotten about, with no record made), or face official (but unspecified) proceedings, which would inevitably result in my being expelled from the course and other, implied, unspecified consequences.

What is a young man, in a police station, accused of unspecified perversions to do? I had not read Franz Kafka’s Der Prozeß (The Trial), but I instinctively knew that I could not win, so I yielded. I intuitively knew that I would stand no chance of getting justice done without a long, expensive and most likely very public legal process, and even then, not necessarily.

Empathy for the suffering of others is, for the INFJ (personality type), second only to their sense of integrity. That integrity was now being besmirched by the most egregious of means, and suspected of unspeakable wrong that anybody with even a passably adequate sense of empathy and compassion for others would not do. In tears, I signed the paper bearing that one, bald line, and I plead to be told what I had done wrong, whether there was anything I could do to make it right, and whether there was any chance of being able to try again at some future date.

I was told that now that I had resigned, the matter was closed and he could not divulge any further information. Reluctantly, though, he did add something about my having followed a female member of the course to her car, but would not elaborate.

I spent months afterwards trying to fathom what he might have been talking about. I could think of only two possibilities: I did, indeed, walk with a middle aged lady to her car, deep in conversation after one of the course days, but it evidently wasn’t that, for by chance I met this same lady in the street some time later. She greeted me warmly, and said that she was sorry that I left the course so suddenly, and that she and the other students had “missed my thoughtful contributions”.

The other possibility is that I happened to follow another course member along an arterial route in my car a short distance away from the police station after one session because that was the direction I happened to be going in. “Followed to her car” is not the same as “followed in your car,” but it’s the only thing that makes any sense.

This woman happened to be a feminist and a lawyer who, I think, specialised in indigenous rights.

The story does not end there. I tried to appeal the decision, but was told that the matter was closed. I wrote to the national oversight body, but was told that there was no case, and anyway, their policy was to back up the decision of the chapter’s management committee. They did, however, refer me to a counsellor to help me deal with the aftermath (at my own cost, naturally).

This counsellor was a piece of work. In our first meeting he reached over while listening to my story and pulled a piece of tape in its dispenser and stuck it to the knurled edge, but did not tear it off just to see, apparently, how long it would take for me to get annoyed and do it for him. Later, he complained about being a counsellor and said that he was probably going to quit the profession. He also said that he thought I might have Asperger’s Syndrome (of which the IT sector has more than its fair share), even though one with this condition would be exceedingly unlikely to volunteer for this work for the reason I did — out of empathy for the victims of crime.

Not only is it a gross breach of professional standards to offer even the suggestion of a diagnosis that he was not qualified to make, this counsellor, it turned out, was an advisor to the very same Victim Support chapter that perpetrated this sorry mess in the first place, but neither he nor the Victim Support guy who referred me told me this beforehand. If I knew then what I know now, I’d have demanded that this guy be struck from the relevant professional register but, as I said, I was young and naïve.

It has taken me over a decade of therapy and time to heal these wounds and although the episode doesn’t haunt me as once it did, I still feel the shame for something I did not do. To this day, I still do not know what provoked all of this. The only reason to speak publicly is the chance it might help other boys and men. That, and because I can’t expect others to be vulnerable and talk about their pain if I’m not prepared to do the same.

Sexual assault is a crime, but naïvety is not.

In His Own Words is an effort to help raise awareness about the invisible victims of domestic violence, men. If you would like to submit your story, please follow the guidelines at the end of this article.

Counseling with Dr. Tara J. Palmatier, PsyD

Counseling with Dr. Tara J. Palmatier, PsyD

Dr. Tara J. Palmatier, PsyD helps individuals work through their relationship and codependency issues via telephone or Skype. She specializes in helping men and women trying to break free of an abusive relationship, cope with the stress of an abusive relationship or heal from an abusive relationship. Coaching individuals through high-conflict divorce and custody cases is also an area of expertise. She combines practical advice, emotional support and goal-oriented outcomes. Please visit the Schedule a Session page for more information.

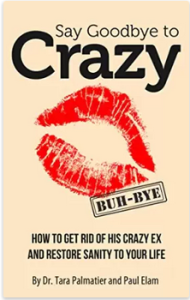

Want to Say Goodbye to Crazy? Buy it HERE.

Want to Say Goodbye to Crazy? Buy it HERE.

Thanks for sharing your story. It sounds like all you wanted to do was be helpful and kind and compassionate. That was a very admirable thing to do and you are to be commended. I’m sorry for what you’ve been through. It’s pretty sick that the victim support guy did what he did… Sounds like he’s been drinking too much feminist Kool Aid.

This story reminds me of a weird situation I ended up in back in 2002, when I was a freshly minted MSW. I ran across a job listing for a “victim’s advocate” for a domestic violence group in Washington, DC. I didn’t actually want to work for them. My speciality in social work is macro; I am more prepared to manage social workers than be a counselor. However, the ad specifically noted that anyone with a degree in social work “need not apply”. I ended up in a very strange email exchange with someone working there when I asked why they were explicitly singling out social workers. It turned out they didn’t want to hire them because the Code of Ethics requires us to report child abusers (but so do many other professional organizations)… The guy who wrote back to me explained that as a social worker, I would have to report child abuse, which would have a “chilling effect” on women trying to get help.

Anyway, basically I came away with the idea that some of these victim’s advocate organizations are all about protecting women as victims, even if they happen to be abusers themselves. Men in a similar situation with SOL… I basically told the guy that his ad was discriminatory and that as a group getting federal funding, that was a no no. So they took off the restriction about social workers, which was probably worse, because these folks would be slaving over their applications and resumes trying to get a job that they would NEVER be considered for because they were social workers.

I am married to one of the kindest, most sensitive guys in the world. Today, he had training that qualifies him to be a casualty support officer in case someone in the Army dies in our area. As he was telling me about his training, he had tears in his eyes… and this is not even something that has affected him personally. But talk to his ex wife, and you’ll hear that he’s a sick, sadistic, pervert who abused her. There is not a mean bone in his body… but his kids think he’s a monster. This kind of persecution against males has got to stop. It reminds me of the whole breed ban hysteria over pit bulls.

Most men are not monsters… but before too long, if the feminists have their way, men will be wearing the sexual equivalent of muzzles in public.

Thanks.

Quite apart from viewing their colleagues and clients through the feminist lens of ‘man bad, woman good’, those guys seem to have some serious deficits in their understanding of professional ethics: Lying about your role in the organisation is both dishonest and unethical. So is lying by omission about the connection between the counsellor and the VS management board. What else did they get up to? In such a sensitive area as victim support, this is a very worrying state of affairs.

I suppose I dodged a bullet, in some ways. On the other hand, I doubt I would have lasted long, even had this not gone down. I have always been and still am fiercely in support of equality and opposed to bullying (since I got so much of it at school), but feminism never sat well with me (probably because the rhetoric seemed at odds with its stated goals), and I probably would not have been able to stomach the PC and misandrist nonsense that I’d have had to deal with.

Your story about the victims’ advocate astonishes me, not least because I would have expected that any professional role dealing with vulnerable people would mandate reporting. For example, isn’t it a matter of law that if, in your perception, suicide is an imminent likelihood or risk, you must contact competent authorities?

Yes, if someone is suicidal or homicidal and expresses intent to carry out suicide or homicide, the counselor does have to call authorities and summon help.

And mandated reporters, which usually include anyone who works with children or other vulnerable people and anyone who might be privy to instances of child or elder abuse (like those who develop film), are legally required to report abuse when they see it. This domestic violence center was hoping to get some kind of legal protection that would loosen the definition of abuse and when it must be reported so that domestically abused women who also happened to be child abusers would be less afraid to ask for help. On one hand, I guess I can see their point… on the other hand, children are always less able to protect themselves than adults are. I have also learned all too well that women can certainly be as violent and abusive as men can be.

The man who corresponded with me explained that they didn’t want to hire social workers because the nature of the victim’s advocate job would require them to violate the NASW Code of Ethics. He said they made their own determination as to when family and child services should be called. Don’t get me wrong. I don’t think it’s always necessarily the best thing to call CPS. A lot of times, kids in foster care end up in a worse situation than where they started. But I did wonder who in the world they had working for them if they were excluding social workers. Social workers are certainly not the only ones who have to report child abuse.

My exchange with the guy from the domestic violence center ended on a rude note. He basically told me to send my resume where it was welcome. Again, I hadn’t actually wanted to work there; I just wanted to know why his job listing discriminated against social workers. Ever since that exchange, I have been turned off of the whole domestic violence cause, even though I know how important it is for those who need help.

I’ve noticed in the last few years that most people I come across have figured out the real feminazi agenda. Left-wing extremism & “liberal” fascism is all it is, at least the stuff that gets media attention. It has contributed to an unjust court system & I say this as a woman. I’ve been reading these blogs for a few days now, and the comment sections. I had no idea there were so many abused men in the world. I’m beginning to feel that my brother is a victim too. What ever can we do to begin to change the family court system, so that it reflects true equality?

you were guilty by association – being a man meant you were an unacceptable candidte – sorry to hear what happened to you and all the fallout from it – sadly the message is if you’re a man don’t bother getting involved because you’re already considered evil or an abuser in waiting at best

I’ve found over the years that a lot of those “victim advocate” groups and shelters are really just money-laundering fronts for feminist political groups. It allows them to receive tax-free funding, run it through the group, and then turn around and use it for lobbying.

Well, when you look at the stats and the problems of violence in our society, this is pretty unlikely. Money laundering? Half the places constantly struggle to stay open. And 501 (c)(3)’s are not allowed to lobby.

I agree with Cousin Dave. Axis II woman have a lobby group, it’s called feminism.